Today is the anniversary of the birth of one of my beekeeper-heroes, Professor Richard Taylor. He was an early champion of the round comb honey system, a commercial beekeeper with just 300 hives, and he was a philosopher who wrote the book on metaphysics. Really, he wrote the book on metaphysics – for decades, his college text Metaphysics introduced first-year philosophy students to the most fundamental aspect of reality – the nature of cosmology and the existence of all things.

Although his sport of philosophy was speculative, unprovable, and abstract to the highest degree, Richard Taylor was as common and down-to-earth as it’s possible to become. I will write about his philosophy and how it shaped his politics, but first, let’s celebrate his beekeeping.

Richard Taylor and his twin brother were born November 5th, 1919. This was shortly after their father had died. That left a widowed mother to raise an impoverished family during the Great American Depression. Richard was fourteen when he got his first hive of bees in 1934 – the year that a quarter of Americans were unemployed and soup-lines leading to Salvation Army kitchens stretched for blocks. He began beekeeping that year, and except for submarine duty as an officer during World War II, he was never far from bees. He respected honest hard work and the value of a penny, but he nevertheless drifted, trying college, then quitting, and taking on various uninspiring jobs.

Evenings, on his bunk in his navy sub, Richard descended into the gloomy passages of Arthur Schopenhauer. Somehow the nihilistic philosopher appealed to Taylor and ironically gave him renewed interest in life. Because of this new interest, Taylor went back to school and became a philosopher himself.

Richard Taylor earned his PhD at Brown University, then taught at Brown, Columbia, and Rochester, from which he retired in 1985 after twenty years. He also held court as a visiting lecturer at Cornell, Hamilton, Hartwick, Hobart and William Smith College, Ohio State, and Princeton. His best years were at Rochester where he philosophized while his trusted German shepherd Vannie curled under his desk. Richard Taylor sipped tea and told his undergrads about the ancient philosophers – Plato, Epicurus, Aristotle, Xeno, and Thales. In the earlier days, he often drew on a cigar while he illuminated his flock of philosophy students. Those who attended his classes remarked on his simple, unpretentious language. They also noted that he was usually dressed in bee garb – khakis and boots – he and Vannie quickly disappeared to his apiaries when the lecture ended and the last student withdrew from the hall.

The hippie beekeeper

It’s probably unfair to call Dr Richard Taylor a hippie beekeeper, but perhaps he was exactly that. As a beekeeper, he was reclusive. He refused to hire help. Rather than deal with customers, he set up a roadside stand where people took honey and left money on the honor system. Taylor disdained big noisy equipment. He claims to have sometimes taken a lawn chair and a thermos of tea to his apiaries so he could relax and listen to the insects work, but I doubt that he did this much. Through the pages of American Bee Journal, Bee Culture, and several beekeeping books, he described best beekeeping practices as he saw them – and those practices required hard work and self-discipline more than relaxed introspection.

Running 300 colonies alone while holding a full-time job and writing a book every second year demands focus. His bees were well-cared for, each producing about a hundred pounds every year in an area where such crops are rare. By 1958, he was switching from extracting, which he disliked, to comb honey production, which he loved. Comb honey takes a more skilled beekeeper and better attention to details, but in return it requires less equipment, a smaller truck, and no settling tanks, sump pumps, whirling extractors, or 600-pound drums. “Just a pocket knife for cleaning the combs,” he wrote.

Running 300 colonies alone while holding a full-time job and writing a book every second year demands focus. His bees were well-cared for, each producing about a hundred pounds every year in an area where such crops are rare. By 1958, he was switching from extracting, which he disliked, to comb honey production, which he loved. Comb honey takes a more skilled beekeeper and better attention to details, but in return it requires less equipment, a smaller truck, and no settling tanks, sump pumps, whirling extractors, or 600-pound drums. “Just a pocket knife for cleaning the combs,” he wrote.

To me, it’s surprising that Richard Taylor embraced the round comb honey equipment called Cobanas. The surprising thing is that the equipment is plastic. Reading Taylor’s books, one realizes his affinity for simple tools and old-fashioned ways. Plastic seems wrong. But it’s not.

To me, it’s surprising that Richard Taylor embraced the round comb honey equipment called Cobanas. The surprising thing is that the equipment is plastic. Reading Taylor’s books, one realizes his affinity for simple tools and old-fashioned ways. Plastic seems wrong. But it’s not.

In the past, comb honey sections were square-shaped and made from wood. That required the decimation of forests of stately basswood (linden) trees, something that did not appeal to Taylor. Plastic lasts forever, a real benefit for a person as frugal as Richard Taylor. It’s light-weight, durable, and ultimately very practical for bee equipment. He advocated making comb honey and he was sure that the Cobana equipment, invented by a Michigan physician in the 1950s, would lead the way. He was so enthused that in 1958, living in Connecticut, he wrote his first beekeeping article about the new plastic equipment for the American Bee Journal. Here’s the photo that accompanied his story.

Richard Taylor’s son, Randy, packing round comb honey, 1958. (Photo from ABJ).

One final thing about Richard Taylor, the beekeeper. He was financially successful. In today’s dollars, his comb honey bee farm returned about $50,000 profit each year – a tidy sum for a hobby and more than enough spare change to indulge his habit of frequenting farmer’s auctions where he’d delight in carrying home a stack of empty used hive bodies that could be had for a dollar.

Taylor, the teacher

Richard Taylor immensely enjoyed teaching and lamented what he called “grantsmanship” which arose in America while he was a professor. Grantsmanship is the skill of securing funding for one’s projects while ignoring the fundamental duties of teaching. This, of course, can eventually lead to big dollars flowing to researchers who are willing to claim that sugar, for example, does not contribute to obesity and cigarette smoke does little more than sharpen one’s senses. Richard Taylor saw the conflict and regretted the demise of good faculty instructors replaced “largely by graduate students, some from abroad with limited ability to speak English. Lecturers who simply read in a monotone from notes are not uncommon,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, the (sometimes unethical) pursuit of grants was accompanied by the rise of the “publish or perish” syndrome. In his own field, Taylor pointed out that academic philosophers engaged in “a kind of intellectual drunkenness, much of which ends up as articles in academic journals, thereby swelling the authors’ lists of publications.” Taylor wrote extensively on this in 1989, saying that there were 93 academic philosophy journals published in the USA alone – seldom read, seldom good, but filling the mailboxes with material to secure a professor’s promotions.

This was not the academic world that Richard Taylor sought when he began his career in the 1950s, but it was the world he eventually left. Although he wrote 17 books – mostly philosophical essays but also several rather good beekeeping manuals – he didn’t publish many academic papers. He spent more time in the lecture halls and with his bees than he did “contemplating the existential reality of golden mountains” and writing papers about them, as he put it.

The philosopher and the bee

I am only going to give this one short passage about Richard Taylor, the philosopher. He studied and taught metaphysics and ethics. His essays on free will and fatalism are renowned and influential, even today. I’ve never taken a philosophy class, so anything I might say here will probably embarrass me. But five years ago, during a winter trip to Florida, I carried Taylor’s Metaphysics with me. I read every word and I think that I understood it at the time. For me, most of it was transparent common sense. Since it was well-crafted and interesting, Taylor may have lulled me into believing that I understood his metaphysical description of the universe, even with just this cursory introduction. At any rate, I felt that what he wrote wasn’t different than what I’d come to discover on my own, although it was much more elegantly presented than I could ever manage.

Taylor-made politics

When I saw Richard Taylor – just once, at a beekeepers’ meeting – I indeed thought that he was a hippie, a common enough form of beekeeper in the 1970s. His belt was baler twine and a broad-rimmed hat hid his face. I was surprised to later discover that Richard Taylor identified as a conservative and voted Republican. But he was also an atheist, advocated for women’s rights, and late in life (though proud of his military service) he became a pacifist, “coming late to the wisdom,” he said. I guess he would be a libertarian today. He valued hard work, self-sufficiency, and independence. He disliked Nixon, but gladly voted for Reagan. He even wrote a New York Times editorial praising Reagan’s inaugural address while offering insight on what it means to be a conservative.

When I saw Richard Taylor – just once, at a beekeepers’ meeting – I indeed thought that he was a hippie, a common enough form of beekeeper in the 1970s. His belt was baler twine and a broad-rimmed hat hid his face. I was surprised to later discover that Richard Taylor identified as a conservative and voted Republican. But he was also an atheist, advocated for women’s rights, and late in life (though proud of his military service) he became a pacifist, “coming late to the wisdom,” he said. I guess he would be a libertarian today. He valued hard work, self-sufficiency, and independence. He disliked Nixon, but gladly voted for Reagan. He even wrote a New York Times editorial praising Reagan’s inaugural address while offering insight on what it means to be a conservative.

At age 62, still a professor of philosophy at the University of Rochester, and the recent author of the book Freedom, Anarchy, and the Law, he wrote a widely-circulated 1981 New York Times opinion piece. Taylor wrote that in Reagan’s inaugural address, Reagan reminded us that “our government is supposed to be one of limited powers, not one that tries to determine for free citizens what is best for them and to deliver them from all manner of evil.” Richard Taylor then goes on to warn that “political subversion . . . is the attempt to subordinate the Constitution to some other philosophy or creed, believed by its adherents to be nobler, wiser, or better.”

Taylor warned of anti-constitutional subversion in American politics, “if anyone were to try to replace the Constitution with, say, the Koran, then no one could doubt that this would be an act of subversion.” He continues, “Similarly, anyone subordinating the principles embodied in the Constitution to those of the Bible, or to those of one of the various churches or creeds claiming scripture as its source, is committing political subversion.”

Taylor tells us that conservative spokesmen of Reagan’s era – he mentions Jerry Fallwell and others – are right saying that “it is not the government’s function to pour blessings upon us in the form of art, health, and education, however desirable these things may be.” Nor, he claims, is it constitutional for “the Government to convert schoolrooms into places for prayer meetings, or to compel impoverished and unmarried girls, or anyone else, to bear misbegotten children, to make pronouncements on evolution, to instruct citizens on family values, or to determine which books can and cannot be put in our libraries or placed within reach of our children. . . it can never, in the eyes of the genuine conservative, be the role of Government to force such claims upon us. The Constitution explicitly denies the Government any such power…”

I think that Richard Taylor would be politically frustrated today. The Republicans have drifted ever-further from small government and have expanded their reach into personal affairs while the Democrats have pushed forward extensive safety nets. A true libertarian party, such as Taylor seems to wish for, gathers little support in America today.

I think that Richard Taylor would be politically frustrated today. The Republicans have drifted ever-further from small government and have expanded their reach into personal affairs while the Democrats have pushed forward extensive safety nets. A true libertarian party, such as Taylor seems to wish for, gathers little support in America today.

I hope that my summary of Richard Taylor’s political philosophy has not offended his most ardent followers. I’ve tried to distill what Taylor thought about good government – I agree with much of it, but disagree with some. It is presented as just one facet of his personality. Taylor was complicated. His last book, written in his 80s while he was dying from lung cancer, is about marriage – yet his own marriages had heartbreaks.

He showed other complicated and unexpected quirks. For example, he was an avowed humanist, yet showed a spiritual nature. In his office, he mounted a certificate which honored him as a laureate of the International Academy of Humanism, one of the few people chosen over the years. Others included Carl Sagan, Christopher Hitchens, Isaac Asimov, Richard Dawkins, Richard Leakey, Steven Pinker, Salman Rushdie, E.O. Wilson, Elena Bonner, and Karl Popper. Taylor belonged there among the other atheists, even if he once metaphorically wrote in his most popular bee book, “the ways of man are sometimes, like the ways of God, wondrous indeed.”

Taylorisms in the bee yard

Richard Taylor was complicated for a simple man. It is said that he could not stand complacency, vanity or narcissistic behavior, yet he seemed to get along well in any gathering. He had a love of paradox and Socratic whimsy, yet he was disciplined and direct as a writer. He delighted in the pessimism of Schopenhauer, yet he was not a pessimist himself. Instead, he was quite a puzzle.

Richard Taylor was complicated for a simple man. It is said that he could not stand complacency, vanity or narcissistic behavior, yet he seemed to get along well in any gathering. He had a love of paradox and Socratic whimsy, yet he was disciplined and direct as a writer. He delighted in the pessimism of Schopenhauer, yet he was not a pessimist himself. Instead, he was quite a puzzle.

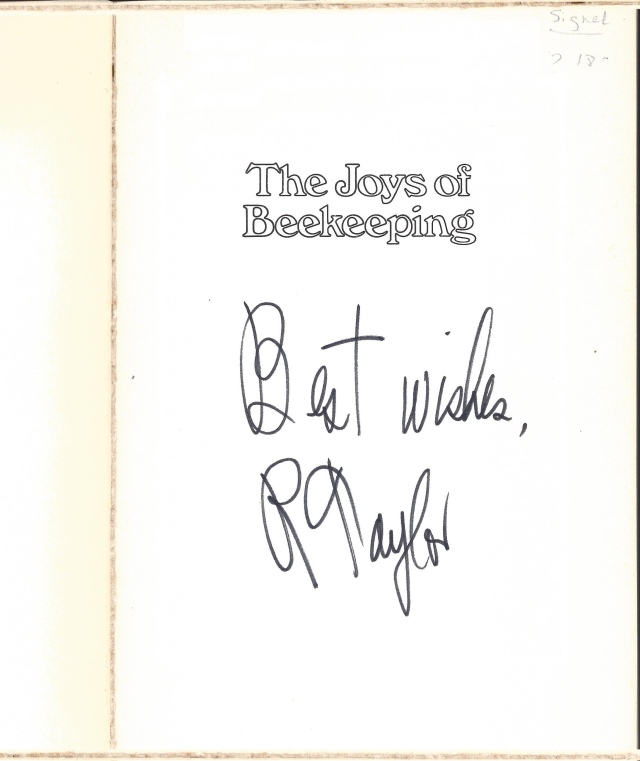

I will end this little essay with wisdom from Richard Taylor, beekeeper. Richard Taylor’s finest bee book, The Joys of Beekeeping, is replete with homey truisms that every aspiring beekeeper should acknowledge and embrace. The book itself is slim, entertaining, personal, and very instructive of the art of keeping bees. Or, as Taylor himself calls beekeeping, “living with the bees. They keep themselves”.

Here, then, are some select Taylorisms:

Beekeeping success demands “a certain demeanor. It is not so much slow motion that is wanted, but a controlled approach.”

“…no man’s back is unbreakable and even beekeepers grow older. When full, a mere shallow super is heavy, weighing forty pounds or more. Deep supers, when filled, are ponderous beyond practical limit.”

“Some beekeepers dismantle every hive and scrape every frame, which is pointless as the bees soon glue everything back the way it was.”

“There are a few rules of thumb that are useful guides. One is that when you are confronted with some problem in the apiary and you do not know what to do, then do nothing. Matters are seldom made worse by doing nothing and are often made much worse by inept intervention.”

. . . and my own favourites . . .

“Woe to the beekeeper who has not followed the example of his bees by keeping in tune with imperceptibly changing nature, having his equipment at hand the day before it is going to be needed rather than the day after. Bees do not put things off until the season is upon them. They would not survive that season if they did, so they anticipate. The beekeeper who is out of step will sacrifice serenity for anxious last-minute preparation, and that crop of honey will not materialize. Nature does not wait.”

“Sometimes the world seems on the verge of insanity, and one wonders what limit there can be to greed, aggression, deception, and the thirst for power or fame. When reflections of this sort threaten one’s serenity, one can be glad for the bees…” – The Joys of Beekeeping

Pingback: Money from Honey 101 | Bad Beekeeping Blog

Pingback: A Metaphysical Life — Bad Beekeeping Blog – Sassafras Bee Farm

Pingback: 2016 in Bee Review | Bad Beekeeping Blog

Pingback: Pinching the Queen | Bad Beekeeping Blog

Pingback: Long Live the (New) Queen | Bad Beekeeping Blog