I’m repeating a blog which I posted on Christmas Day last year. It’s about the inventor of modern beekeeping, L.L. Langstroth. Enjoy!

Langstroth, 1810-1895

He invented modern beekeeping, making it easier, more productive, and less stressful for bees. However, Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth earned nothing from his invention and suffered severely from self-doubt, melancholy, and clinical depression. Yet, he changed beekeeping to its core and on his birthday anniversary (Christmas Day!) we give homage to the most important beekeeper America ever produced.

Langstroth was born December 25, 1810. That was some Christmas gift to the world, wasn’t it? His childhood seems to have been typical for a kid who spent a lot of time on his hands and knees on the streets of Philadelphia, trapping bugs and ants with table scraps. “I was once whipped because I had worn holes in my pants by too much kneeling on the gravel walkways in my eagerness to learn all that I could about ant life,” Langstroth wrote.

He built paper traps for beetles and flies, leading to a traumatic experience when his grammar school teacher – fed up with six-year-old Lorenzo’s wasted bug time – smashed his paper cages and freed his flies. Lorenzo was sent to cry himself to sleep inside a dark cupboard at the school. The teacher’s reform strategy worked. Langstroth gave up his interest in insects and became a preacher instead.

Langstroth’s Andover church

Langstroth studied theology at Yale. At 25, he was offered a job as pastor at the South Church in Andover, Massachusetts. Even in Langstroth’s day it was an old prestigious church. In 2011 it celebrated its 300th anniversary. The plum assignment pastor at South Church – was a recognition of the young man’s abilities.

While visiting a parish member, Langstroth noticed a bowl of comb honey. He said that it was the most beautiful food he had ever seen. He asked to visit his new friend’s bees. Langstroth was led to the fellow’s attic where the hives were arranged near an open window. “In a moment,” Langstroth remembered, “the enthusiasm of my boyish days seemed, like a pent-up fire, to burst out in full flame. Before I went home I bought two stocks of bees in common box hives, and thus my apiarian career began.” Langstroth had been bitten by the bee bug.

Head troubles

Throughout his lifetime, Langstroth suffered badly from manic-depression. In the mid-nineteenth century there was little anyone could do to help a person afflicted with mental illness. The only solace was temporary and usually came to Langstroth when he was with his bees.

The young minister felt that he wasn’t an effective parson because of his recurring dark days, so he quit preaching and became principal of a women’s school instead. By all accounts, he was a empathetic minister and a dedicated teacher, but bouts of depression forced him to cancel sermons and classes. He needed a change. Bees were the only thing he knew that could give him peace, comfort, and meaningful work and also fit into a life disrupted by his debilitating illness. But sometimes not even bees could stop what he called his “head trouble” when darkness crept upon him.

He built an apiary and hoped to make his living from bees. But that summer, severe depression returned and lasted for weeks. He sold all his colonies in the fall. Then he started with the bees again. His life would turn over again and again with periods of manic enthusiasm and productivity followed by gloomy months of despondency. During his depressed phases, Langstroth took shelter in a bed in a dark room. He would remain there, immobile, for days. “I asked that my books be hidden from my sight. Even the letter “B” would remind me of my bees and instill a deep sadness that wouldn’t leave.”

When he was able to return to his bees, Langstroth made great strives at increasing his efficiency in the apiary. He learned to innovate and to make his tasks more effective. He would never know when depression would return so he worked day and night during his highly productive manic periods.

Eureka!

The major inefficiency in the apiary was the design of the boxes which held his bees. The boxes were usually simple wooden crates with solid walls and small holes which the bees used as entrances. During harvest of a hive, the lid was lifted from the crate. Attached to the lid would be wax combs which the bees built in haphazard jumbles. The combs cracked and broke during the beekeeper’s excavation, causing a sticky mess and disturbing the excited bees. It was a messy, nasty way to inspect bees and harvest honey.

Langstroth noticed that bees often left a small space around the edge of their combs. Sometimes, upon lifting the lids, he would find wax attached to both the lid and the walls inside the hive, while at other times the hanging combs were not stuck to the hive walls at all. Langstroth’s brilliant insight (his Eureka! moment) was to notice that the space was about 3/8 of an inch when the combs hung freely. If a comb were closer than that to a wall, the bees would seal it. But at 3/8 inch (actually, between 6.35 and 9.53 mm), the bees always left a space. He had discovered “bee space”.

Langstroth’s next step was brilliant. He made wooden frames that held the wax combs. The frames dangled within the hive’s box so that their wooden edges were always 3/8 of an inch from anything that might touch the frame – the lid, the interior box walls, the box bottom, other frames. Positioned like this, the bees neither waxed the frames together nor to the sides or bottom of the hive. The result was a beehive with movable frames. Combs could be lifted, examined, and manipulated. It was 1851 and modern beekeeping had begun.

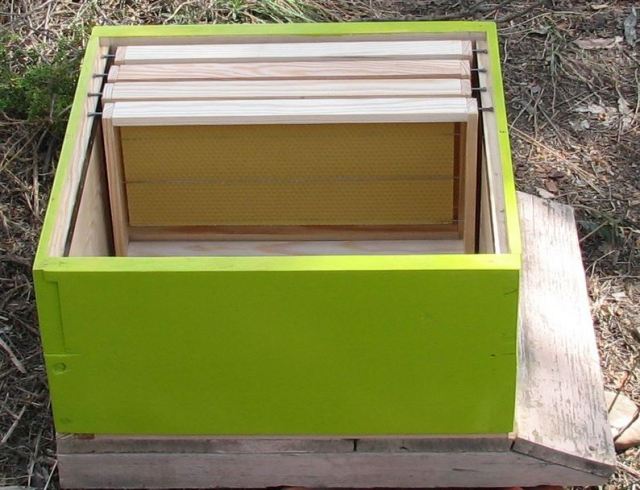

Langstroth frames, the heart of his invention (Source: R. Engelhard)

Colonies could be handled more gently. Frames could be inspected for disease, queen quality, and honey and pollen reserves. Movable frames meant queen bees could be produced and strong hives split (by sharing frames between two or more new hives) – increasing colony numbers while preventing swarming. It was a new era in beekeeping. The next few decades are still known as “The Golden Age of Beekeeping“.

Easy to use, easy to make, easy to copy

L.L. Langstroth was not alone in figuring out bee space and inventing applications for it. About the same time, some European beekeepers (Huber, in Switzerland and Dzierzon in Poland/Germany, Prokopovich in the Ukraine, among others) had made similar discoveries. But Langstroth created a simpler and more easily used hive. His Langstroth beehive was a fine example of North American utilitarian craftsmanship. Efficient, simple, and cheap.

Langstroth’s invention was so simple and cheap that his patent was readily violated. Minor modifications were touted as significant improvements to Langstroth’s original design, circumventing the patent. Langstroth began a number of lawsuits against the more flagrant violators, but when the court cases began, his “head troubles” returned.

He dropped the litigation when he realized he could not win and when his illness prevented a spirited defense. Realistically, it was impossible to stop imitations and adaptations. Beekeepers – who were often handy farmers and carpenters – quickly built one or two hives with frames for themselves. Langstroth sought one dollar to license each box, which was a huge price in those days. But his real discovery was “bee space” which could not be patented. His position was like trying to patent sails for ships after discovering wind. Even Langstroth’s supporters wrote that Langstroth should have simply allowed the idea to flourish in the public domain. Trying to enforce the patent was expensive. It left Langstroth nearly bankrupt.

Frames, dangling in a hive. (Source: D. Feliciano)

With a plethora of modifications and with similar boxes being designed in Europe, Langstroth’s great contribution may have entered the world anyway and without much credit to him. But the retired minister had one other major contribution to society. It earned him much-deserved praise and even a bit of money. In one feverish manic spell that lasted six months, Langstroth wrote one of the greatest beekeeping books ever produced.

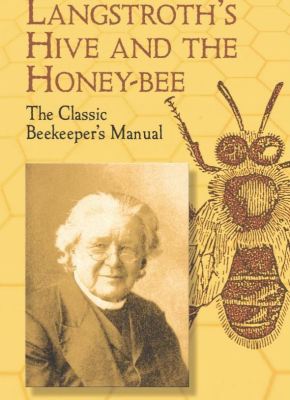

Hive and Honey Bee

Modern copy of Langstroth’s 1853

Hive and Honey-Bee

In 1852, working for six months without stop and almost no sleep, Langstroth wrote The Hive and the Honey-Bee. This book, revised and expanded in more than 40 subsequent editions, is still one of the most reliable sources for beekeepers. When Langstroth wrote it, there were other good bee primers on the market, but his book moved to the top spot. You may read the original 1853 book on-line. I’ve read and re-read my 1859 copy with its 409 pages of fading text protected by orange hardboard covers. It earned its spot in my library. Within the book are chapters on Loss of the Queen (and what to do about it), Swarming, Feeding, Wintering, and Enemies of the Bees. It’s a very practical guide to keeping bees and much of it is still relevant today.

Langstroth never had lasting peace from his cycles of manic depression, though in his 60s he traveled to Mexico and found that the stimulation and change of scenery gave him an unexpected respite from depression. The illness returned when he returned to his home, but he remembered the break from head troubles with great appreciation. He lived long enough (85 years!) to see his work appreciated, his name honored, and his book sell hundreds of thousands of copies. Despite his life-long disability, he had a long, full life, three children, and interesting work. And he made a phenomenal contribution to beekeeping.

Merry Christmas and Happy Birthday,

Lorenzo Loraine Langstroth!

Reblogged this on Beekeeping365 and commented:

Excellent read!

LikeLike