In mid-March, Stevo Sun, a Calgary resident, sent some gorgeous pictures of honey bees foraging on silver maple. Maple is an ornamental here, at our elevation and latitude. But for less than $250, you can pick up a young tree and drop it into your Calgary yard. I’ve seen some nice maples, now approaching 20 or 30 years in age – so, with care, they can survive our dry climate, short summers, and long cold winters. It may surprise some readers that maples don’t grow in every corner of Canada. There are parts of Canada where the maple appears only on flags, not in every front yard. For ubiquitousness, the bumble bee would have been a better symbol on our flag.

The maple and bee photographs were taken March 16, two weeks ago. That was a mild day, but not warm. (It was around 14 °C, 57 °F.) Our local internet chat group was buzzing with reports of pollen sightings. Optimism swept the city. But after that pleasant respite, the temperature fell far below freezing. Natural pollen didn’t return for ten days. The I saw tiny dots of pollen in one bee’s baskets, but I didn’t want to embarrass the little worker by taking a picture of her and her sad dab of pollen.

The maple and bee photographs were taken March 16, two weeks ago. That was a mild day, but not warm. (It was around 14 °C, 57 °F.) Our local internet chat group was buzzing with reports of pollen sightings. Optimism swept the city. But after that pleasant respite, the temperature fell far below freezing. Natural pollen didn’t return for ten days. The I saw tiny dots of pollen in one bee’s baskets, but I didn’t want to embarrass the little worker by taking a picture of her and her sad dab of pollen.

Pollen supplement: Saving the bees?

Because our spring is always slow arriving here in Calgary, I began feeding pollen supplement on March 26. Some readers may have begun in February. Today, the temperature here is a few degrees warmer than it had been in mid-March when the first pollen arrived. Colonies are brooding up quickly, with a several frames of open brood in each, but nary a speck of stored pollen. I placed some large pollen cakes (15% pollen with vegetable proteins) right above the brood. I have no doubt that this will be eaten within ten days and then I’ll be adding the next pollen supplement.

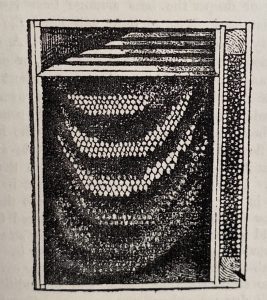

We recommend that beekeepers continue feeding pollen supplement (and honey or sugar, too) continuously until after the main spring flow starts and the weather is stable. A break in pollen supplement accompanied by a few days of bad weather may result in worker honey bees killing and eating much of their brood due to the lack of protein to feed it. In the next two pictures, you can see how nice the brood was on March 26, but looking closely, note the absence of pollen near the brood. Honey stores (about four frames) were nearby, but being consumed quickly. These bees needed food and I gave it to them.

Nice brood for our area in March.

Close-up: note the absence of pollen and honey stores.

Here in the Calgary area, we feed pollen supplement at this time of the year because spring weather isn’t reliably mild. The first teaser of natural pollen may be followed by days of freezing temperatures (it was this year). Honey bees aren’t flying enough to bring in the massive amounts of protein it takes to build their population. But I have another reason for feeding pollen supplement to honey bees. It might surprise you.

In most locations, it is almost impossible to overstock an area with honey bees during the peak flow. But before and after that brief time, there might not be enough pollen for all the bees in the area, resulting in stiff competition among bee species for a limited amount of food. This is especially true in the spring, when honey bees and native bees are building their brood nests. An overwintered honey bee hive will expand from almost no brood and ten thousand bees to ten frames of brood and forty thousand bees in two months. Observant beekeepers tell us that it takes one frame of pollen and one frame of honey to grow each frame of brood.” This would require about thirty or forty pounds of pollen to build the colony’s spring population.

In most locations, it is almost impossible to overstock an area with honey bees during the peak flow. But before and after that brief time, there might not be enough pollen for all the bees in the area, resulting in stiff competition among bee species for a limited amount of food. This is especially true in the spring, when honey bees and native bees are building their brood nests. An overwintered honey bee hive will expand from almost no brood and ten thousand bees to ten frames of brood and forty thousand bees in two months. Observant beekeepers tell us that it takes one frame of pollen and one frame of honey to grow each frame of brood.” This would require about thirty or forty pounds of pollen to build the colony’s spring population.

Back-of-the envelope math suggests that if one colony of honey bees consumes thirty pounds of pollen, they will need to find 40 to 60 billion grains of pollen. With an estimated 50,000 pollen grains per flower, honey bees visit something like one million flowers to achieve this. Grain size and a flower’s pollen production rate will add a lot of variation to this number, of course. But you already see the point – supplying honey bees with pollen supplement will reduce a colony’s use of wildflowers and perhaps lessen its impact on native bees.

Leave some for the other bees.

.

.

.

.

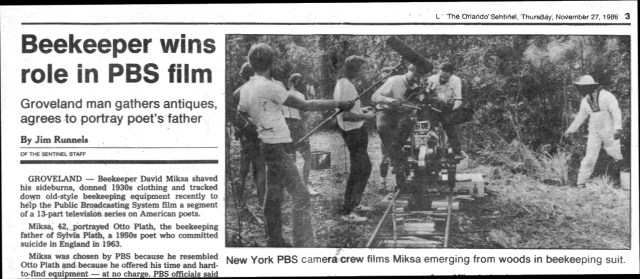

Plath struggled for years with her severe depression. And with her unconventional perspective on the landscape of our lives. And with her sheer brilliance and talent. A 160-IQ can be hard to focus. Her paintings won awards. Posthumously, she was honoured with a Pulitzer for her poetry. An over-achiever, she had worked as a successful model and had kept a journal from age 11. Near the end of her brief life, she kept honey bee hives in her English garden. Finally, she was mum to her children,

Plath struggled for years with her severe depression. And with her unconventional perspective on the landscape of our lives. And with her sheer brilliance and talent. A 160-IQ can be hard to focus. Her paintings won awards. Posthumously, she was honoured with a Pulitzer for her poetry. An over-achiever, she had worked as a successful model and had kept a journal from age 11. Near the end of her brief life, she kept honey bee hives in her English garden. Finally, she was mum to her children,

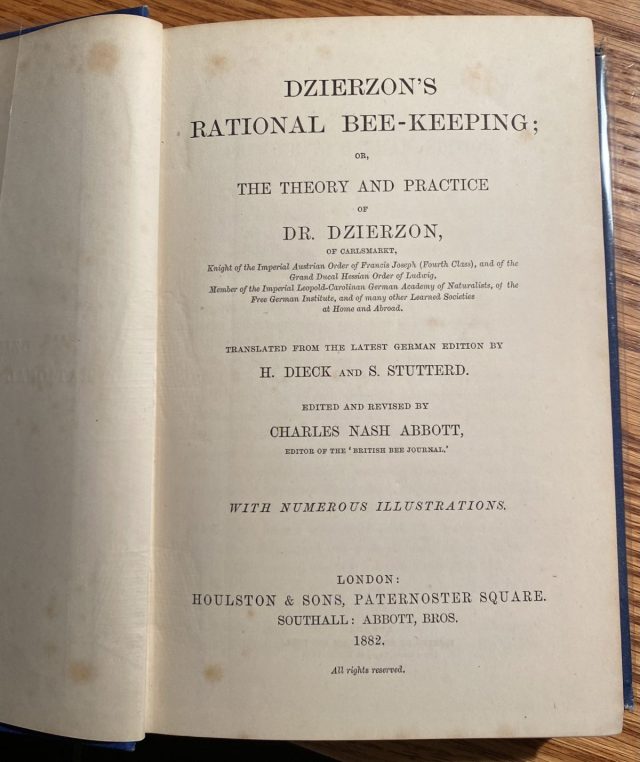

You know how the mention of a name from long ago can bring back memories that you thought had slipped away forever? I had that experience recently. Browsing

You know how the mention of a name from long ago can bring back memories that you thought had slipped away forever? I had that experience recently. Browsing  Crownvetch was “discovered” by my first-ever boss, George Sleesman, the director of Pennsylvania Plant Services. Sometime in the 1950s, the state Department of Transportation asked Sleesman to find a plant that might be a good, attractive, low-management creeper to prevent erosion on the deep roadway cuts through the Appalachians. Sleesman, the state’s chief apiary inspector, scoured the Pennsylvania hills for sturdy plants that could hold eroding road embankments in place. Crownvetch caught his eye.

Crownvetch was “discovered” by my first-ever boss, George Sleesman, the director of Pennsylvania Plant Services. Sometime in the 1950s, the state Department of Transportation asked Sleesman to find a plant that might be a good, attractive, low-management creeper to prevent erosion on the deep roadway cuts through the Appalachians. Sleesman, the state’s chief apiary inspector, scoured the Pennsylvania hills for sturdy plants that could hold eroding road embankments in place. Crownvetch caught his eye. If you have a few minutes, listen to Kirsten Traynor and Calvin Ernst as they discuss the growth of interest in native plants and Ernst’s role in making such seeds available. You can download the show (Season 3, Episode 26) from your favourite podcast provider, or hear it

If you have a few minutes, listen to Kirsten Traynor and Calvin Ernst as they discuss the growth of interest in native plants and Ernst’s role in making such seeds available. You can download the show (Season 3, Episode 26) from your favourite podcast provider, or hear it