I’ve written about ‘creamed’ honey before, but I think it’s time to mention it again. I don’t know what you call smooth honey – some folks call it creamed (though no dairy products are involved), spun (though no spinning is involved) or smooth (which it certainly is!). If you had a nice crop of honey this year, you might like this way to present honey. Fall is the natural time to make creamed, or spun, honey. Your main season is over, the weather is turning chilly, and cool weather helps the fine-granulation process that results in great creamed honey. And creamed honey will certainly boost your sales.

Brenda and Mike with some of their creamed honey

These friends of mine, Brenda and Mike, make great creamed honey. The bees are kept in the Rocky Mountain foothills where the honey is usually mild and light. Brenda handles the honey smoothing at her home.

I’ll give you Brenda’s recipe:

It’s actually pretty simple. Heat the honey until it’s completely liquid with no granulation crystals left in it. Cool it to room temperature and stir in some creamy ‘seed’ honey. Stir and stir and stir. Pour it into the final containers and store it in a cool place. The seed can be creamed honey from your previous batch of creamed honey. If this is your first year making the stuff, you’ll have to get some creamy (“spun”) honey at the grocery or from a friend. After that, keep some in reserve for the next crop. People use from 5 to 20 percent seed, but most add about 10 percent.

Once ‘creamed’, the honey will stay this smooth for months – or even years.

Selling granulated honey is tricky. If it crystallizes slowly, big grainy chunks form. If moisture is a bit high, the water and honey may separate after packing, with a layer of sour fermenting honey-water floating above large, unattractive grains. Because most of the honey here in Canada granulates quickly, beekeepers learned to pack it in pails with wide lids, making the honey accessible after the inevitable hardening. This became known as “real” honey while honey that stayed liquid (which was rare) was suspected of being overheated or adulterated. That’s why, even today, crystallized honey is more common that liquid honey on grocery shelves in Canada.

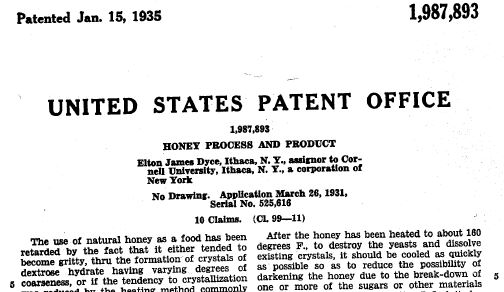

But granulated honey sometimes spoils because it’s usually not heated enough during packing to kill yeast. Another common problem is the growth of over-sized granulation crystals (if honey crystallizes slowly over several months, the crystals are bigger). Poor quality granulated honey was common in the early 1900s. At the time, most Canadian honey was packed in gallon-sized tins and sent off to England. After producing, packing, and shipping across the ocean, beekeepers sometimes weren’t paid – the buyers in London had to dump the stuff as it had soured or had a watery layer on top. A young Canadian ag-scientist, Elton Dyce, recognized the problem and spent years looking for a fix.

But granulated honey sometimes spoils because it’s usually not heated enough during packing to kill yeast. Another common problem is the growth of over-sized granulation crystals (if honey crystallizes slowly over several months, the crystals are bigger). Poor quality granulated honey was common in the early 1900s. At the time, most Canadian honey was packed in gallon-sized tins and sent off to England. After producing, packing, and shipping across the ocean, beekeepers sometimes weren’t paid – the buyers in London had to dump the stuff as it had soured or had a watery layer on top. A young Canadian ag-scientist, Elton Dyce, recognized the problem and spent years looking for a fix.

Dyce was working at the Ontario Agriculture College (now known as the University of Guelph). In the 1920s, he taught apiculture to farm kids who came to the school from across central Canada. They told him about the honey that went bad back on the farm. From their samples, he noticed that finer-granulated honey had less moisture-separation problems. And it generally tasted better.

At age 28, Elton Dyce moved to Cornell University in New York to work on a Masters’ in entomology. Until he developed his system, most efforts to improve honey focused on heating it. This resulted in longer-lasting liquid honey, but Dyce felt that such honey wasn’t what consumers wanted on their tables. At Cornell, he continued to work on the Canadian honey problem. Three years later, he filed US Patent 1987893, simply called “Honey Process and Product“. He began his patent claim by stating that the use of honey is inhibited because it can be gritty and inconsistent unless heated. Then, he said, such liquid honey becomes drippy and harder to use. Dyce had a better idea. In paragraph 4 of his claims, Elton Dyce spelled out his system:

4.) A honey product made by heating honey to a temperature sufficient to destroy yeasts, quickly cooling it to a temperature below the melting point of honey crystals preferably about 75 degrees F., adding about 5% of fine grained crystalline honey, agitating the honey to distribute said nuclei uniformly thruout the honey, and controlling the temperature within a few degrees of 57 degrees F., whereby a fine-grained, fondant-like product is formed.

That’s the entire method, now known as the Dyce Process: Heat honey to destroy yeast, quickly cool it to 75 ºF, uniformly mix in fine-grained crystallized honey (‘seed’), and store it at 57 ºF. Quite soon, your honey is a smooth, fine-grained fondant. At this stage, the honey is attractive, ships well, and won’t spoil.

Dyce’s patent was issued 80 years ago and has long-since expired. Anyone may now use his technique to make perfect, tasty, smooth honey. My friends Brenda and Mike proved that to me.

*Part of the preceding is from my 2016 American Bee Journal article.

Pingback: Creamed Honey | Raising Honey Bees

This sounds easier than I thought. Brenda’s recipe doesn’t mention rapid cooling being necessary as the Dyce process does. Should the heated honey be put in a fridge or just left at room temperature?

LikeLiked by 1 person

She simply places it in an unheated part of her basement as soon as it’s mixed. (About 15 C) It’s ready in ten days to two weeks. The mixing is a lot of hard work, even with a big electric mixer.

LikeLike

I’ll definitely try it! Thanks!

LikeLike

i wish i could find a frig that stayed at 57F……:(

LikeLike

A lot of people use a cellar or basement floor.

LikeLike

No cellars or basements in central Texas

LikeLike

Can you live without creamed honey?

LikeLike

Perhaps you should move? That’s another solution.

LikeLike

Jackass …psh….

LikeLike

Yeah, you’re right. Sorry about that.

LikeLike

We have a kitchen aid mixer. Should we use the paddle or whipper attachment ?

LikeLike

We use the whipper.

LikeLike

I did larger quantities 25 pounds in a 5 gallon pail… using my 3/4 drive drill with a 5-Gal size ‘paint stirring attachment’. Worked like a ‘charm’…

LikeLike

What if I were to use crystallized honey & runny honey. Can this work? What she’ does this process look like

LikeLiked by 1 person

Basically, crystallized plus liquid honey is the formula. You want to use very finely granulated (smooth small crystals) honey and room temperature honey that has absolutely no crystals in it. Stir very thoroughly and chill at about 10C (50F) and wait a week or two.

LikeLike